Saturday, August 14, 2010

Transmutation*

In the spring of ’85, school children collecting frogs from a pond in Minnesota discover one frog after another with deformities. The story gains notoriety, capturing the attention of national media.

*

Last night I dreamt my mother owned a wooden globe. This globe charted no territory. It was plain. My mother kept it on her desk and would sit for hours, admiring its simplicity.

*

Gretchen smoothes wool over her face. She is interested in the imprint her features leave in the soft fabric. She is a sculptor.

*

Ferdinand Tönnies was not widely known as a religious man. Religion, or as he saw it, a common mental community, did not impose itself on his methodology. Between the years of 1921 and 1933, he wrote many of his nine hundred works in a vestry.

*

My grandmother arrived in New York in 1937. She was 19. She’d traveled from Palermo, Sicily. The boat that brought her was called the Rex. It sprang a leak and sank in the early eighties. By then, my grandmother had been married for almost fifty years.

*

“It’s ’84,” he tells her, “when my dad gets off his ass and gets a job.”

“Doing what?”

“He sold medical equipment. Then through his long-time buddy, pops becomes a VP at Shasta Cola. In those days, if you knew someone, you could become an executive. This ex-football player, probably not even played a full season, he was an executive at Shasta. Don’t remember much about him except he was black and humongous. He didn’t have a corner office. Pops had a corner office. Corner office with a view. He’d take me there and we’d look down on all the people like we were staying at the Standard. Sometimes, we’d throw harmless objects at the little people.”

“He had his moments.”

“Doing what?”

“He sold medical equipment. Then through his long-time buddy, pops becomes a VP at Shasta Cola. In those days, if you knew someone, you could become an executive. This ex-football player, probably not even played a full season, he was an executive at Shasta. Don’t remember much about him except he was black and humongous. He didn’t have a corner office. Pops had a corner office. Corner office with a view. He’d take me there and we’d look down on all the people like we were staying at the Standard. Sometimes, we’d throw harmless objects at the little people.”

*

Tönnies classifies all human relations into two types: organic and mechanical. Those he sees as organic, spring from Gemeinschaft. Family, kinship, community, and intimate relations make up Gemeinschaft. Mechanical contraptions are the relations of Gesellschaft, which are imaginary and constructed. Public life, society, the coexistence of independent people: these make up Gesellschaft. Gesellschaft artificially resembles Gemeinschaft.

*

My grandmother, Maria, immigrated to marry. She married Louis, who worked in a shoe factory. Theirs was a marriage arranged by family. When Louis claimed Maria at Ellis Island, they were wed immediately, right there on a pier with hundreds of witnesses. He was not disappointed in his new bride. She was beautiful and could only speak Sicilian. Later, they’d renew their vows in a formal ceremony in a church, before God.

Aboard the Rex, Maria had met a young man, also traveling to New York from Sicily. This man was called Nicola. He occupied the cabin next door to Maria. All night, Nicola would play the ukulele. He played until his fingers bled. Later, he’d become a successful entertainer. But not yet. Aboard the Rex, his playing drove passengers mad, especially the old woman who shared Maria’s cabin. This old woman told Maria to knock on the ukulele player’s door. She told her to tell him sta’ zitto!

*

Gretchen ambles down Fifth. She thinks about the word amble as she does it, as she is self-conscious, but not in the usual ways. Today, she wears a white hat and white gloves, and white ankle boots. Her sunglasses are dark. She has nowhere to be.

*

Ferdinand Tönnies was born into a wealthy farmer's family. He published many of Thomas Hobbes’s manuscripts. Tönnies shared Hobbes’ vision of society as lacking direct authority, but existing as the constant tension between people.

*

Last night I dreamt my mother had a lantern growing out of her head. The lantern was shaded by rose-colored glass. The light the lantern let off was grainy, deceptive, evocative of Parmigianino. All is illuminated.

*

Maria enjoyed the music. She took Nicola on deck so he could play uninterrupted. Though it was night, the water was not black. She asked him to play Stranger in Paradise and O Solo Mio. Nicola was happy to oblige. Maria liked it up deck. She was excited to go to America, to marry an important designer of women’s shoes. Nicola frowned to hear that she was promised to another. Since he was a gentleman, he took her hand and placed it on his chest. He would’ve liked to kiss it. Maria unclasped her purse and took out a letter. She let Nicola copy its return address.*

A year after she wed on a pier off Ellis Island, Maria gave birth to my mother. Maria described my mother as a good baby, one who didn’t cry often. One April morning, my mother, sick with the shingles, cried for four hours straight. When Nicola heard these sounds, the sounds of a child, he turned back. He left the flowers on the mat without knocking on the door. Into his palm, he folded the slip of parchment that read 8905 Avenue M. He would write a song about that morning and call the song, “Too Little Too Late.” Years later, after my mother had found him, and after she’d arranged for Nicola to play my grandparents’ fiftieth wedding anniversary, together, we all raised glasses, salut! And he sang us the song.*

You want to make a connection, but there’s no connection to make. What you know to be a frog is really a mutant. Without mutations, the species will never evolve.*

Last night my mother took her own mother in her arms. Leads her to the sink and sits her down before it in a large wicker chair. Since Maria is so feeble, my mother cushions the seat with many pillows. My mother runs the tap until it is warm, and then fills the bowl with warm water. The bowl is porcelain, yellow from use and with history. Maria asks for a towel to drape her neck. My mother gets her one, and while in the bathroom, opens a bottle of shampoo. She stands there for a moment to inhale its simple smell. When my mother returns to her, Maria is laughing. My mother squeezes the bottle and a glob of shampoo lands in her hand. She lathers up her mother’s head with palmfuls of warm water. This was not in a dream.

*

“Like what? What kind of objects would you toss out the window? Feathers? Confetti? Strange behavior for a father to advocate.”“He had his moments.”

*

The understanding of human will is essential to understanding Tönnies’s vision of social groups. In Gemeinschaft, authority arises from the common will and is therefore reciprocal. All for one; one for all. This type of will binds humans to a totality. Within the social group, each individual is free to exercise his or her own will, and further, each individual will dictates function and privilege.*

Last night I dreamt my mother was held at gunpoint by a bandit. He told her she had two minutes to live, ten minutes to die. She asked him how he knew she was a traveler, and one by one her tears fell into the River Styx.*

Gesellschaft destroys the idea of a unified will. In place, Gesellschaft fosters relations built upon the exchange of commodities. Commodities can be tangible objects (a coin, a pineapple) or abstract activities, like labor. Worst of all, the vision in Gesellschaft is distorted: people appear to be working for totality, but are in fact pursuing their own interests.

*

You want the “I” to trump all other stories, to offer grounded footing, a point of reference. But that would be selfish of me, wouldn’t it?

*

Gretchen stops at a water fountain in Washington Square Park. She is too well dressed to drink from the water fountain at this park. The water tastes secretly delicious. She takes off her sunglasses and gloves so she can enjoy the park, its grasses and beady-eyed squirrels. She doesn’t mind that she is without a blanket. She takes off her clothes. She likes to feel the blades of grass imprinting her body. A flock of mimes sitting cattycorner offer naked Gretchen some of their reefer. The cops arrest Gretchen and the mimes flee.

*

Last night I dreamt my mother was sitting in a wooden chair. She had a plastic bag over her head with a label that read: keep away from children.*

In the back of a cop car, a police officer asks Gretchen if she’s on anything aside from a couple puffs of pot. She’s fully dressed now. In the back a cop car, she wears handcuffs instead of gloves. She doesn’t cry or beg for freedom. The officer writes up a citation.*

Last night my father danced in a church. The church was domed with a high, curved ceiling. Candles lit up the window glass, stained with picaresque stories. A smoke machine churned smoke down the aisles. In, out of the aisles, my father danced. Then a comet tore through the window. Glass everywhere. The comet split my father in two. There was much blood and then he was fine. Head of a man, trunk of a beast. This was in a dream.

*

Some of the malformations are horrific, like the one-eyed frog found in a Wisconsin wetland. Others are comedic. Like the frog with three eyes found in a swamp in Macon, Georgia. New York Harbor turns up frogs with too many hind legs. Others had reached adulthood without ever shedding their tails. The EPA gets involved.

*

Gretchen often thinks about her sick father. He once wrestled a hog to its death. Now he resides in assisted living. It’s a nursing home and Gretchen can’t bear to see him there, so she never visits. That doesn’t stop her from thinking about him.

*

“Bloodbath at the Zoo,” she tells him. “’86.”

“Oh yeah?”

“A boy was mauled to death. The story made the news. Some sixth grader jumped right on in while she was tending her cubs. He must have been the type of boy who thinks he could handle a bear.”

“A she-bear?”

“I guess cause he’s throwing cookies, he gets excited. Obviously he has problems with impulse control. At that moment, who knows? Maybe the igloo with its tended garden looked like home. Maybe the boy mistook the bear for a long lost relation.”

“What?”

“Stranger things have happened."

“I wonder if authorities shot the bear.”

“Animals,” she tells him, “usually get punished in circumstances like these.”

“Oh yeah?”

“A boy was mauled to death. The story made the news. Some sixth grader jumped right on in while she was tending her cubs. He must have been the type of boy who thinks he could handle a bear.”

“A she-bear?”

“I guess cause he’s throwing cookies, he gets excited. Obviously he has problems with impulse control. At that moment, who knows? Maybe the igloo with its tended garden looked like home. Maybe the boy mistook the bear for a long lost relation.”

“What?”

“Stranger things have happened."

“I wonder if authorities shot the bear.”

“Animals,” she tells him, “usually get punished in circumstances like these.”

*

Amphibian malformations continue to be reported. Over 60 species in 46 states. With each report, the story changes. Marine biologists can’t agree on a cause: ultraviolet radiation, says one; another points to water contamination. The latest report touts parasites. No one suggests the end is near.

*A version of this story appeared in [sic] issue one, 2006

The Dream

Henri Rousseau is one of my favorite painters. I saw this painting, The Dream at the MoMA when I was about 8 or 9 and I had a very strong reaction to it.

The Dream epitomizes Rousseau’s technique of unexpected juxtapositions, predating the Surrealists, before the style was in fashion. He liked to joke that he’d been born in the wrong century. His contemporaries playfully called him Le Douanier after his lifelong career as a customs officer.

In the painting, the moon denies the movement of the sun, the succession of day to night. Like dream, the painting exists in a state removed from time. By 1910, when Rousseau painted The Dream, just months before his death, people understood dreams as falling within one of three types of wish fulfillment, all involving elements of disguise. In the first class, the wish is presented in successful disguise and the sleeper enjoys a pleasant dream. In the second, the disguise is unsuccessful or absent. The forbidden desire emerges causing anxiety, and the sleeper wakes up disturbed. The third class of dream presents content that is disturbing, but the feeling is not. In this manifestation, the wish is disguised by a misalliance and juxtaposition of content and feeling.

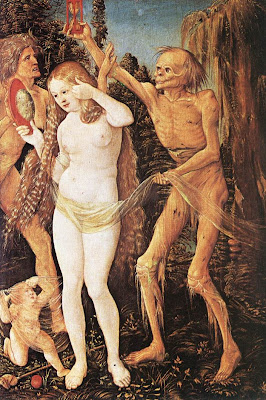

La Vanite

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)